What is the WEF? Part One: The Fourth Industrial Revolution

By Justin Aukema

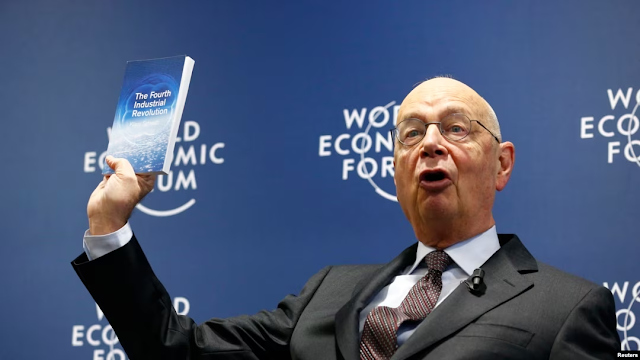

Klaus Schwab, head of the WEF, wrote The Fourth Industrial Revolution in 2016. Much of the book echoes discourse now common among business and political leaders. Readers will instantly recognize its ideas since they are already a part of common parlance. As with much of the WEF program, it is difficult to determine who is setting the agenda in the first place. Do WEF publications like The Fourth Industrial Revolution make the rules which others follow or are they simply repeating words and ideas that are already common among elites? Perhaps a bit of both.

The key focus of the FIR is technology and how it’s transforming the ways in which we live. In Schwab’s view, the FIR is the culmination of a series of three prior industrial revolutions. It is characterized by AI and machine learning especially. But its potential impacts are even more disruptive than the previous three he argues. For that reason, it’s crucial for “stakeholders,” he says, to come together and decide how best to utilize the new transformations. The WEF sees the world as composed of “stakeholders” which include “governments, business, academia, and civil society” (8). The concept allows Schwab and others to both discount class struggle especially but also even nation states, and instead to reify the current social order. Different classes are sublimated under the category of “civil society,” while “business” is elevated to the same footing as governments. Each of these should have equal shares or stakes in decision making, Schwab implies. Meaning that the locus of popular sovereignty is removed from the populace and even their elected representatives and instead placed in the hands of a technocratic and unelected elite. This carries on earlier trends of blurring the lines between public and private, state and non-state, from the neoliberal regime.

The genius of the FIR lies in its subtle approach. It takes increased technology and digitization as a given. And it also claims that the transformations will be highly disruptive. But the reality of what it is proposing is in fact almost the opposite in that it reifies the current order. The effects of technological change in other words are always only ever analyzed within the stakeholder framework which is an assumed constant. But this stakeholder model itself is never challenged. How will stakeholders deal with the changes? How will governments adapt? How will individuals respond? And so forth. It is the selective nature of the questions themselves which are setting the very discursive framework. It’s akin to asking someone who likes neither pizza nor hamburgers which one they want for dinner. The actual preferences of the reader hardly matter, since the outcome is already decided. So in the context of the FIR, AI, synthetic biology, increased surveillance, inequality, and so on will incontrovertibly happen. The rest of the text thus concerns itself with altering our perceptions so that we see these things as beneficial rather than detrimental.

The second chapter “Drivers” makes this clear. The chapter discusses how blockchain, IoT, and digital currencies are already here and shaping the ways we live. But I will focus mainly on its treatment of biomedical tech. The FIR notes the “breath-taking” “innovations” in this field including DNA manipulation like the “ability to edit biology,” as well as xenotransplantation, bioprinting organs, designer babies, and neurotechnology (24-26). Having already established that these things will happen, the FIR thus simply concerns itself with how to direct them “towards the best possible outcomes” (26). Here its “solutions” simply build on the old neoliberal and stakeholder model. University research programs for example should become more “commercial” by cooperating with corporations while governments should devote more money to high-tech R&D.

Chapter Three, “Impact,” simply drives this same point home. The changes will be “disruptive” it says. So, the solution? Simply that “empowered actors” should “recognize that they are part of a distributed power system that requires more collaborative forms of interaction to succeed” (31). Once again, therefore, the solution reinforces the true point of the FIR which is to sublimate class and other struggles into the stakeholder vision of the world. Power is diffuse. There’s therefore no point fighting back against it. And it most certainly doesn’t lie with the ruling capitalist class. Etc. This is the point and that the FIR attempts almost entirely through sleight of hand.

The goal and aim of the FIR therefore is thus not simply to praise technology but to reify the current class order. Or, perhaps it should be said, to even further cement and empower this order and to impoverish the working and middle classes. As evidence of this, the FIR proposes a backwards vision of the historical-materialist conception of history. If the original HM identified capitalist social relations acting as a fetter on future productive powers, the FIR praises and seeks to strengthen this very fetter itself. Technology in this view is predicated on the endless production and consumption of commodities and thus wage labor (i.e. capitalist social relations). But this is portrayed as a net positive because it will reduce them to “zero marginal costs” meaning they are “essentially free” (35). This is the same logic promoted by economists like Jeffrey Rifkin and Paul Mason who, failing to perceive capitalism as a social relationship, mistakenly equate falling commodity prices with “post-capitalism.” The reality is actually the opposite: further degraded labor and intense power consolidation resembling techno- or neo-feudalism.

The FIR reluctantly acknowledges at the same time what Marxists would call the tendency of the rate of profit to fall. This is the understanding that only variable capital (worker’s labor power) and not constant capital (machines, tools, etc.) can create the surplus value that capitalism relies on. For this reason, however, the FIR proposes to turn social problems into profitable experiences. So-called “negative externalities” like climate change, for instance, therefore are recast in a positive light as new “green” investment opportunities, while unemployment caused by automation could be countered with a “capitalization effect” by simultaneously creating new jobs (36, 38). It is true admits the FIR that automation will replace many jobs. But we shouldn’t fear this says its author. Rather we should embrace the “fusion of digital, physical and biological technologies” which can “enhance human labor and cognition” and “work alongside [...] intelligent machines” (43). In the mid-19th century, Marx feared that technology was forcing humans to work like machines. Now, in the 21st century, Karl Schwab and others are arguing that we go a step further and literally become fused with machines!

But of course the FIR doesn’t just want our bodies. It also wants our minds, too. “Minds” in this sense refers to cognition and human behavior which in machine terms of zeros and ones simply boils down to one word: data. The FIR is thus a race for data which is almost equivalent with value itself. Since real productive value has almost been entirely replaced with other fictitious forms, techno-capitalists thus need to tap not only our labor power but also our emotions and desires for future profit too. “The ability to tap into multiple sources of data – from personal to industrial, from lifestyle to behavioral,” says the FIR “will be a necessary part of the value proposition” (55, 54). And how is this achieved? Of course by the only means possible the FIR admits: “constant monitoring” (56). This means not only more precise measurements of abstract labor but also the forms of surveillance capitalism envisioned by Shoshana Zuboff and others.

Now this might seem like a grievous encroachment into our personal lives. While we might not own a whole lot, at least our minds and our bodies are our own, right? Well, as Marx already explained 150 years ago, not exactly. That’s because the creation of a proletariat is predicated on owning nothing but one’s own labor power. And even that we are forced to sell! The FIR understands this well and, like other techno-feudalist proponents of the “sharing economy” continues to knock away at the last vestiges of any form of ownership at all. “An increasing number of consumers no longer purchase and own physical objects, but rather pay for the delivery of the underlying service which they access via a digital platform,” explains the FIR, noting a shift from “ownership to access” (58, 61). This is where the idea of “you’ll own nothing and be happy” comes from. The ideologues behind the FIR and elsewhere are actively undermining all forms of private property and ownership which were once considered essential for the existence of liberal-democracy itself. In the future, we really will have “nothing [left] to lose but [our digital] chains.”

This is also what the WEF and others mean by a “circular economy,” a term that, ironically, has also been picked up by many on the Left. Circular economy in this sense does not mean producing for actual human need instead of profit. Instead, it means using new technologies and “new efficiencies” to eliminate “waste” and thereby generate more new value. Eliminating “waste” here includes all forms of austerity and degrowth strategies as well such as “entic[ing] people into consuming less” and getting people to move to a sharing economy rather than one based on ownership (65).

The FIR then shifts back to the roles of governments and states in the “stakeholder” capitalist vision. As mentioned, neither governments nor the people are the locus of power under this scheme, but are simply relegated to one actor or stakeholder among many others including especially businesses. In this sense, the role of governments is to create favorable business conditions. This is a hallmark of neoliberalism as noted by David Harvey and thus I argue the FIR simply carries on the neoliberal project. Furthermore, I argue that this is taken a step further as the new role of government is also to secure corporate profits amidst a sharply declining rate of profit and crisis of value creation. The FIR states that “increasingly, governments will be seen as public-service centres that are evaluated on their abilities to deliver the expanded service in the most efficient and individualized ways” (67). The “service” referred to is a combination of consumer-governance functions such as healthcare for instance or any other form of “public” service. Such services are relegated to private corporations and monitored by tech companies. The role of the government is simply to create the necessary legal framework and encourage forced compliance into the digitally monitored system. So, the use of health-tracking apps, e-government, and digital currencies, for instance, are all examples of this. Moreover, in the process, says the FIR, governments “will be completely transformed into much leaner and more efficient power cells, all within an environment of new and competing power structures” (67). Although “leaner” evokes images of neoliberal austerity programs, this does not mean state power itself is in any way diminished. As the FIR explains, it is rather strengthened and made more efficient through the use of digital tech, the removal of traditional democratic civil liberties, and the emergence of the corporate-state enterprise.

Ok, so now we have an idea of what the FIR is all about. But wait a minute, what if we don’t want this vision of the future the FIR has already claimed is basically inevitable anyway? Well, the outlook is not hopeful for such critical minds. This is because the FIR portrays opponents to its “progressive” program basically as neanderthals at best and potential terrorists at worst (86). “The greatest danger to global cooperation and stability” it says, will come from “radical groups fighting progress with extreme, ideologically motivated violence” and operating out of “ignorance.” (86). Sure the world is “very unequal,” the FIR admits. And technology is only going to make it more so. On top of that, robots almost certainly will take your jobs (87). Not to mention the “very real danger” that governments might employ this new tech to crush civil liberties and impose authoritarian regimes. But hey, all we can do at this point, hints the FIR, is just get on board with the program. Why try to stop the tide or move against the current? It’s futile anyway right? And if we do get on board, the benefits are so great, it tries to convince us. Why be part of the losers when we can join with the winners, those “who are able to participate fully” in the new system “rather than those who can offer only low-skilled labour or ordinary capital” (87). Hey, the “winners may even benefit from some form of radical human improvement [...] (such as genetic engineering) from which the losers will be deprived,” the WEF tract even explains (92). Hot diggity-dog! That barcode neck-implant or robotic spleen you always wanted is just around the corner. And all you have to do is cede the last vestigate of your individual freedom to the emergent corporate-state enterprise, i.e. “Society 5.0.” How much simpler could it get?

As the FIR concludes, the best thing is not to be too critical. After all, that just gives headaches. What we need instead is the right kind of “intelligence” it says. A “pervasive sense of common purpose” based mainly on “sharing” and “trust” (101). Trust here of course refers to our stakeholder overlords (of which we are purportedly a part). Don’t think too much; don’t question; just get on board with the FIR. If we do that “we can [...] lift humanity into a new collective and moral consciousness based on a shared sense of destiny” (105). So ends Schwab’s visionary text. But what is the destiny? What is the vision? In fact, there is none. The “destiny” is none other than embracing the program of the FIR itself. That’s why this sentence comes at the end; it needs no further explanation because it has already been explained.